THE PATHS

WE FORGE

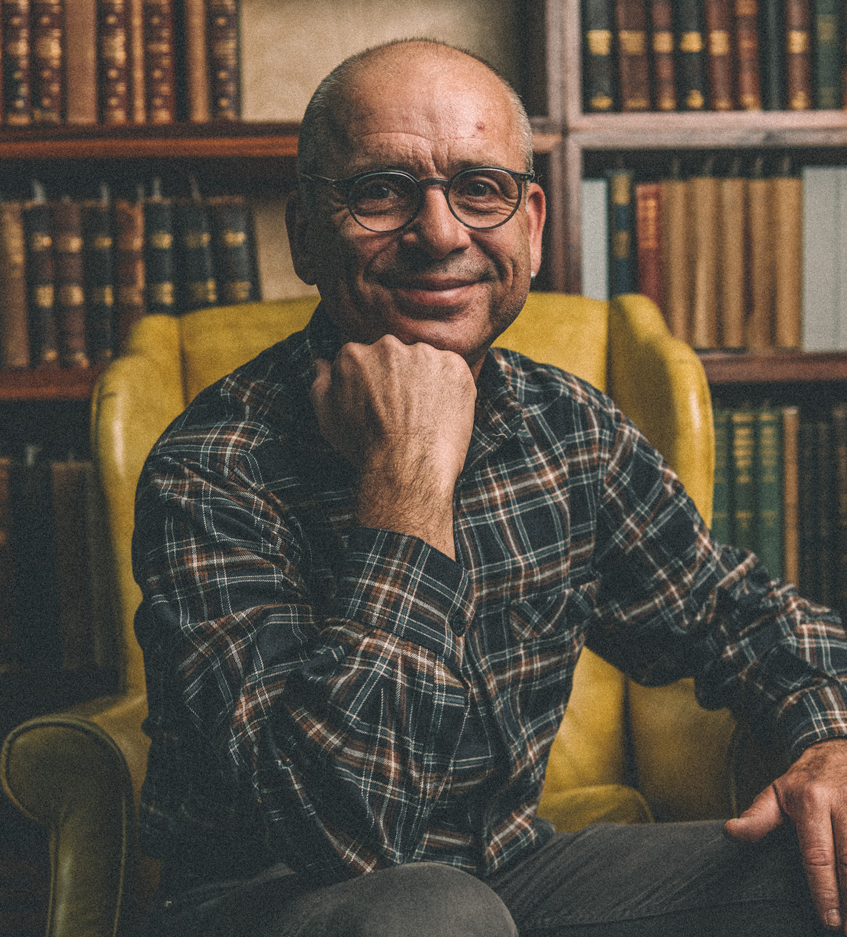

MARKUS DAMWERTH

Teaching What’s Been Forgotten

Markus Damwerth finds inspiration in wood. The material itself is what Markus loves most

about carpentry.

“If you have a piece of plastic, or metal you can just cut it any way you want,” he says. “But when you work with wood, you have to look at that piece of wood and see, okay, is it straight? Is it bent? How would it move in the future if it moistens up or dries? From there you can decide what can be built out of this piece. It's a very creative work, and this is what I like.”

As a kid in Germany, Markus used to help his dad and grandfather with the carpentry business his grandfather had started in the 1930s, crafting windows, doors, cabinetry, and interior woodwork for both buildings and ships. Through this experience and the apprenticeship that followed, Markus learned—and learned to appreciate—the time-honored ways of doing things, the old techniques that are often overlooked today in favor of cheaper, easier methods and mass production. Self-employed through most of his career, he continued to grow this base of knowledge through an inspired curiosity and desire to learn.

Now, Markus keeps these techniques alive as Professor of Architectural Carpentry at the American College of the Building Arts in Charleston, South Carolina. Founded partially in response to the destruction of much of Charleston’s historic architecture by Hurricane Hugo in 1989, the college teaches classical architecture and design, woodworking and architectural carpentry, timber framing, and blacksmithing.

“We combine a four-year liberal arts college education with a trade education, and that is unique, he says. “100% of our graduates have a job even before they graduate. It’s not only about learning the trade. They also learn all the background: material sciences, leadership, how to set up a business plan, how to organize a business.”

Markus describes the subject he teaches, architectural

carpentry, as woodwork that’s attached

to, but not a

structural part of a building. It’s things like windows,

doors, paneling, molding,

and staircasing.

“Traditional architectural carpentry is woodworking without a nail gun,” he says. “We always use techniques which fit the natural material, and wood is special. Wood moves. It has a certain cell structure, so you have to know about the material and the joinery which you could use.”

Some of the joinery techniques he teaches date back thousands of years, to the Romans even, and are prevalent in much of the very old architecture of Europe. Many of these techniques have nearly been forgotten, especially here in the United States. Markus believes this is due to the fact that many of the craftsmen using them in the U.S. throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries were immigrants who had brought their knowledge with them.

Markus cites the Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris, much of which was destroyed in a 2019 fire, as a prime example of this type of craftsmanship. The building lasted for centuries and would have lasted for centuries more if not for the fire. Modern tools and techniques wouldn’t be capable of repairing the damages, so the restoration effort takes the abilities of people like Markus. In fact, a graduate of the American College of the Building Arts is even involved in this effort.

Markus has grown to love teaching just as

much as he loves carpentry. He says it

feels good to

take the knowledge he’s

acquired in 40 years of on-the-job

experience and instill it in the next

generation of young people who are hungry

to learn. He also enjoys how much he himself

learns from teaching others.

“Nothing teaches more than teaching,” he says. “It's not only that I teach my students; I recognized that by explaining what I do to others, I have to question what I do myself. I always discover a new solution, a better way to do things.”

Markus’ favorite thing to build, though, doesn’t fit into the architectural carpentry category he teaches. It’s just good, old-fashioned woodworking. Markus loves building tables, for the craft challenges they pose, but also for what they represent.

“A table is where people meet,” he says, “and they meet at a table for dining, for work, for celebration, or for mourning. Building tables is not only an interesting thing trade wise, it's also interesting to look at a table and say, okay, what purpose does this table serve? What might happen at this table? And this is something I like very much.”

SHOP NOW >

SHOP NOW >

SHOP NOW >

SHOP NOW >